Overview

In the complex world of governance and policy, few instruments wield as much influence over economies and societies as the public budget. Whether we find ourselves in times of resource constraints or facing the unsettling specter of conflict, budgetary decisions have a profoundly resonating impact on the well-being of countries.

The Covid-19 pandemic, with its far-reaching economic consequences, has left nations grappling with unprecedented challenges. Simultaneously, the war in Ukraine has triggered substantial complications in world trade. In the face of such complex and interconnected crises, the International Budget Partnership's Open Budget Survey in 2021 sounded the alarm. It asserted that as nations strive for sustainable and inclusive recovery, the arena where these pivotal decisions will unfold is none other than public budgets (International Budget Partnership, 2021, pp.10-11).

Imagine recovery and resilience-building as a chessboard on which only a select number of moves are possible. In times of scarcity or conflict, every allocation, cut, or investment becomes a strategic move. The decisions made within the confines of the public budget can determine whether a nation emerges resilient or succumbs to the challenges at hand.

Lebanon, which is still dealing with the consequences of the 2019 economic crisis which resulted in a staggering 98% devaluation of the Lebanese Lira, (World Bank, 2023) is in dire need for skillful “chess players”. This is particularly relevant given the fact that Lebanon has adopted, in 2024, a budget law outlining an ambitious zero-deficit balance sheet , meaning that the government pledged to not run any part of its yearly operations through debt or bond financing. This ambitious yet hardly realistic plan, however, collides with a daunting reality. That is why it is essential to keep in mind the bottlenecks that may derail such an ambition, ranging from political pressure, to data and capacity shortages, to public institutions operating outside of the budget.

A Process Fraught with Landmines

Delving into Lebanon's annual budgeting process offers a glimpse into a yearly financial exercise that involves a multitude of players, including the Ministry of Finance, spending entities, the Council of Ministers, the Court of Audit, and the Parliament. From its initiation in April until its adoption in December or January of the following year, every month unfolds a chapter in the budgeting journey, one that is, alas, fraught with challenges.

Nothing illustrates this point better than the lack of economic forecasts in the budget circular issued by the Ministry of Finance in April. Or that the budget is being voted with no closing of accounts or auditing reports submitted by the Court of Audit since the year 2000 and meaning that parliament has been voting new budgets unconstitutionally and without the formal audit and closure of the previous ones for twenty-four years.

Or that the budget doesn’t capture the whole of it. Lebanon’s budget is not comprehensive, which means that the finances of many public institutions are not included in it, creating risks that very few are aware of. With a large number of entities operating outside of the budget , the government is bound to face financial surprises on a regular basis. That’s no recipe for transparency. It is, however, a recipe for the creation of “black boxes” within government.

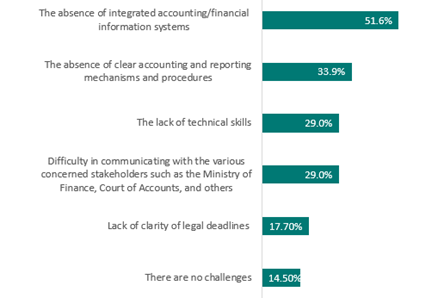

Figure 1: Main Challenges Facing the Accounting and Financial Reporting Procedures

Source: Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan (2022), Rapid Impact assessment of the crisis on Lebanese State Institutions[JB1] .

Old Habits Die Hard

Lebanon clings to an outdated form of budgeting, one that is known as “line-item budgeting”. In simple terms it means that the focus is mainly on where the money is going, not on what it's achieving. The problem with this approach is that it doesn't connect spending to objectives or to services, making it hard to keep an eye on how well things are working (or not).

While many countries have upgraded their budgeting practices by incorporating programs-based approaches, Lebanon’s budget law continues to be a mere accounting exercise, that is not put at the service of any strategic vision for the country.

Data Shortages, Capacity and Currency Hurdles

Laws and tools don’t work by themselves. They need people and systems to make them work. Unfortunately, the loss of talents at the Ministry of Finance and across the public administration, and the depletion of hardware and software have taken a toll on the overall financial management of the country, and on the budget process. Dispersed (and sometimes missing) fiscal data and non-integrated information systems have undermined accountability and the budget’s credibility at large. The fact that no integrated whole-of-government financial management information system is in place makes the planning, cash management, and reporting capacities of spending entities extremely difficult to mainstream, track and report on.

Is there a way out of the weak capacity quagmire?

To put is shortly, yes. A new budget isn’t only about updating laws, but about updating mindsets, building the “buy-in” of stakeholders including Members of Parliament and Civil Society. It is a reform that needs to be “engineered and championned” and not confined to a new legislative text. Until then, immediate steps that could be rolled-out include:

A Fresh Start for Core Functions: Reinforcing institutions that are a bit behind the curve could score some rapid wins. The Macro-Fiscal Unit, for instance is a prime example of such an institution – it's the Ministry of Finance’s go-to department for crunching economic and fiscal figures, and yet it’s in need of urgent capacities. Simultaneously, the Integrated Financial Management and Information Systems (IFMIS) still needs to be adopted across government. That's where the key to shaping a budget that tracks all of the money coming in and going out of the State lies.

Streamlining Organizational Procedures: That would mean that all of the government, including public institutions, would rely on the same forms and documents for budget preparation, needs and expenses reporting. If to that were to be added tools allowing for the prediction of long-term needs, then institutional financial data could be more easily plugged into an all-of-government information system.

Strengthening the Budget’s Coverage: It’s imperative to tackle the challenges of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in order to restore their financial health. Templates and guidelines could be applied the same way they would apply to central government agencies, including the reporting of international aid received. This would unfold side-by-side with capacity development and training programs, and functional reviews. Ultimately, this would allow for the government to capture the “big picture” and move towards a more objectives-based budget more smoothly.

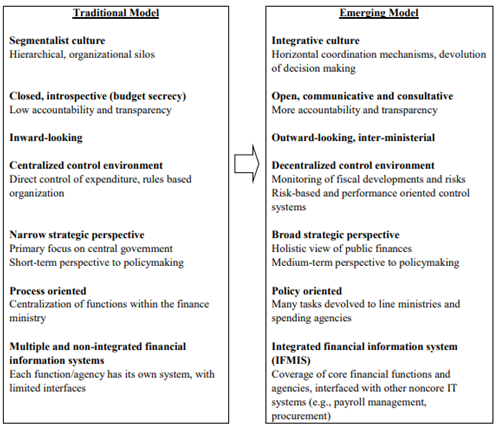

Change Management: Accompanying the Ministry of Finance’s transition towards a more objectives-based model is key, one that is outward-looking, consultative and policy-oriented.

Figure 2: Emerging Role and Culture of Finance Ministries

Source: IMF, The Evolving Functions and Organization of Finance Ministries, 2015

Consolidate both revenue mobilization and expenditure planning and prioritization, including a review the entire revenue structure of the country (link to previous blog) and the use of spending reviews to identify gaps and inform reallocations (link to SP budget review).

This blog was edited by Carl Rihan, PhD. based on policy work conducted by Lamia Moubayed Bissat, President of the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan and Sabine Hatem, Chief Economist and Director of Cooperation and Partnerships.